Table of Contents

Divine Kantara Mythology—A Deep Mythological Guide about Bhoota Kola Festival & Dieties Panjurli and Guliga in English

Why “Kantara Mythology” resonates: The soul of Kantara is not fantasy—it’s rooted in the Daiva traditions of India’s southwest coast, especially the Tulu-speaking region of Tulu Nadu (coastal Karnataka and parts of Kerala). Here, communities have, for centuries, honored guardian spirits (locally called Bhūtas/Daivas) through powerful night-long rituals like Bhoota Kola/Daiva Nema. These traditions blend devotion, oral epics, dance, community justice, and ecological ethics.

Imagine a moon-bright night on India’s southwest coast. The air is sweet with coconut and incense. Drums begin—measured, then quickening. In a forest clearing, a performer steps out: face painted in luminous reds and golds, anklets singing, sword and bell flashing. The crowd hushes not because they’re watching a show, but because they’re waiting for someone—a guardian spirit—to arrive.

This is Bhoota Kola (also called Daiva Nema), the living ritual world that Kantara glimpsed on screen. But the real story is far older, deeper, and more local than a film can hold. It is a covenant between village and shrine, forest and field, human and more-than-human. Tonight we walk into that world—respectfully, enthusiastically, and with both heart and clarity.

Note: This article explains beliefs with respect. It neither judges nor ranks traditions; it simply clarifies origins, symbols, and meanings so readers gain deeper cultural understanding.

Where the story lives: Tulu Nadu’s Daiva world

On India’s southwest coast—Tulu Nadu (Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, parts of Kasaragod-Kerala)—communities venerate guardian spirits (Daivas/Bhūtas) who safeguard land, water, forests, and social harmony. The living heart of this tradition is Bhoota Kola / Daiva Nema—nightlong ceremonies that blend devotion, oral epics, dance, costume, music, oath-taking, and community arbitration. (MAP Academy)

Related: 11 Amazing Life-Changing Lessons from Bhagavad Gita for Modern Life (2025 Guide)

What is spirits/Daivas : A plural world of spirits/Daivas—ancestral figures, animal-guardians, and culture heroes—who protect land, water, forests, and moral order.

In this coastal moral imagination, the world has three interlinked realms: forest ⇄ village ⇄ spirit. Disturb one, and all three tremble. When harmony frays—by deceit, greed, or ecological damage—the Daiva is invoked to set it right. This is why the rituals feel both intimate and vast: they are devotional and civic, personal and ecological.

Why it matters for Kantara: the film didn’t invent a myth; it brought a local sacred universe into the national imagination—especially the paired guardians Panjurli and Guliga, whose ethics are tied to land and truth. Recent scholarship even reads Kantara as a decolonial spotlight on indigenous ecological knowledge. (MDPI)

Why Kantara resonated:

Bhoota Kola and Daiva Nema are not cinematic inventions. The film reverberated because it amplified a local sacred universe—especially the paired guardians Panjurli and Guliga, whose ethics are tied to land and truth. Audiences across India recognized something they longed for: a way of life where oaths bind, land remembers, and community stands together.

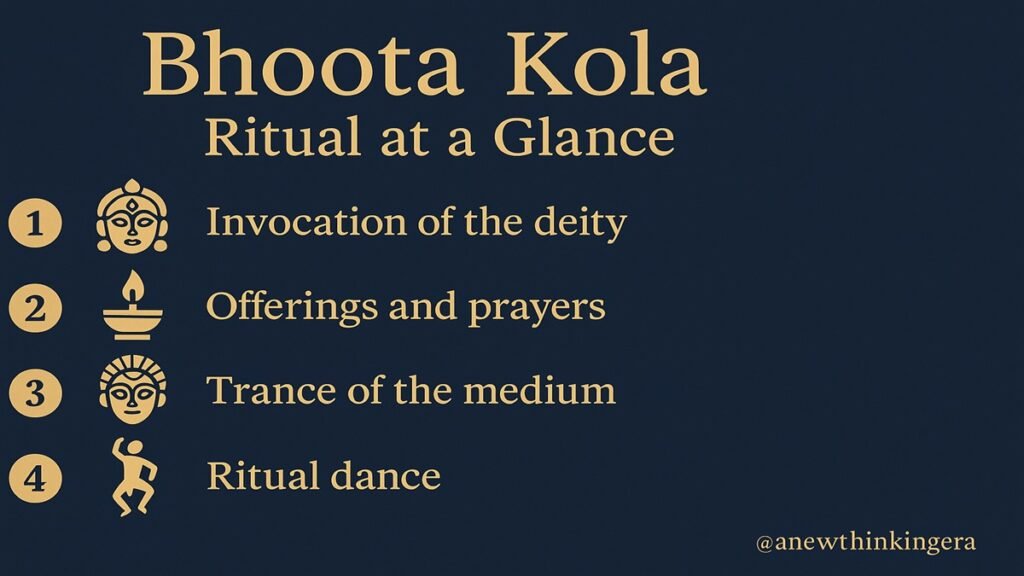

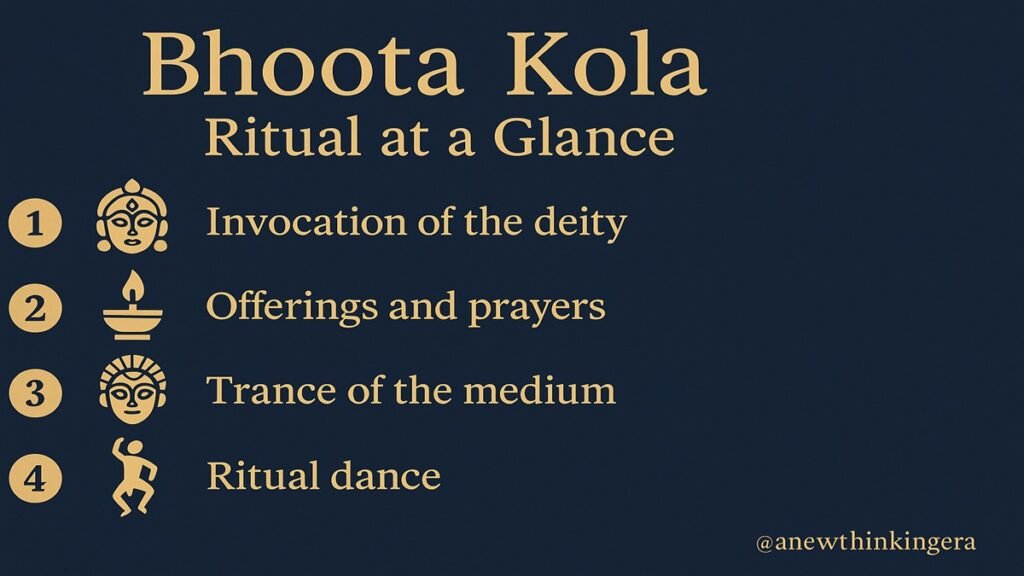

2) Bhoota Kola Festival/ Daiva Nema: the ritual script (as devotees describe it)

Bhoota Kola isn’t a “dance show,” and it isn’t theatre in the entertainment sense. It is ritual: a carefully sequenced performance of arrival. As the night unfolds, the medium (pātri) is ritually prepared—costume, paint, anklets, weapons, and the towering mudi headgear, encircled by a radiant ani (halo). Drums, pipes, and cymbals weave a soundscape that guides the medium toward embodiment. At a recognized moment, the community believes the Daiva descends—and from then on, the words spoken are the Daiva’s counsel.

Read: Powerful Seneca Quotes on Life, Time, Happiness & Stoic Wisdom (2025 Guide)

Importantly, practice varies by village, shrine, and lineage. Some sequences invoke a single spirit (Kola), others call multiple Daivas in hierarchical order (Nema). There are also processional or household forms you may hear named Bandi or Agelu-Tambila, each with its emphasis, offerings, and steps. These are not contradictions; they are the living diversity of a regional tradition.

The Ritual Night, Explained Step by Step—So You Can Feel It

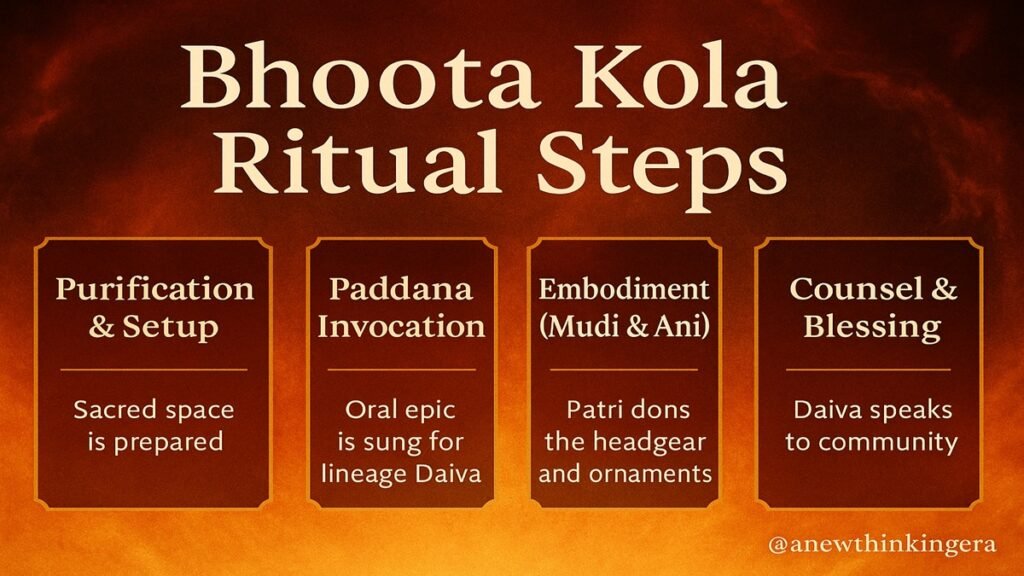

While forms vary by village and lineage, an archetypal Kola/Nema unfolds in stages:

- Purification & setup

The shrine and arena are prepared; oil lamps and torches blaze into life. A date is fixed by local custom. Seasonal cycles matter, and many ceremonies cluster between December and May in the coastal calendar. - Invocation through epic song

Singers begin the paddana—long, sung oral epics that recount the Daiva’s origins, journeys, vows, and the village’s obligations. These aren’t “lyrics” so much as social memory performed aloud. - Alankara (embodiment)

The medium is dressed and armed. The mudi and ani signal a threshold: once worn, they announce not a character but a presence. Gestures with sword and bell, the click of anklets, and circling of the arena ritually redraw the boundary between grove and settlement—reminding everyone that this land has guardians. - Darśana & counsel

Villagers bring petitions: family disputes, crop troubles, oath-making. The Daiva hears, asks questions, sometimes rebukes, often blesses. In many places, the night is understood as a sacred court of justice—a community forum under spiritual authority, not a spectacle. - Blessing & closure

Offerings are made; vows for the coming year are recorded; a sense of mutual duty is renewed. The rite closes not with applause but with the quiet recognition that order has been re-stitched.

Local typologies note related formats—Kola, Nema, Bandi, Agelu-Tambila—each with its own emphasis and sequence. (Wikipedia)

The People Who carries the tradition of Bhoota Kola: lineages, roles, responsibilities

The rite is sustained by hereditary artist-priest communities—often identified in the region as Nalike, Pambada, Parava, among others—who train for years in movement, costume, shrine etiquette, and the distinctive speech registers used during counsel.

Patron lineages (the guttu houses) historically sponsored the rites; even as social structures have shifted, the contract between shrine and village remains remarkably strong. Sponsorship is not mere funding—it is service to a sacred ecology.

Around the medium, a whole ensemble works: drummers, singers, torch-bearers, attendants who manage costume changes and safety. No one is “backstage.” Every role is devotional and communal.

Read Related: 51 Lord Krishna Quotes That Illuminate Life, Love & Divine Wisdom (2025 Guide)

Paddanas: oral epics that keep the village’s moral memory

If Bhoota Kola is the body, paddanas are the breath. These long, sung narratives—performed in Old Tulu cadences—carry origin myths, land histories, lists of vows and duties, and the stories of how particular Daivas came to be guardians of particular places. Scholars treat paddanas as a primary source for understanding Tulunadu’s cultural memory; collectors have documented multiple Panjurli paddanas that cover both genesis and diffusion across the region.

Crucially, paddanas are not frozen texts. They’re living epics, flexible in phrasing, steady in values. A verse may shift, but the ethical spine—truth-telling, promise-keeping, restitution—remains. When paddanas are sung, the village remembers who it has promised to be.

Function: the paddana legitimizes the shrine, articulates the Daiva’s vows, and lays out the ethical constitution of the village—what truth means, how promises bind, what repairing harm looks like.

What paddanas do for a village

- Legitimize: ground the shrine’s authority and the Daiva’s vows.

- Educate: pass ethics across generations without a classroom.

- Map: name fields, springs, groves—turning geography into memory.

- Heal: narrate wrongs and reparations, keeping justice humane.

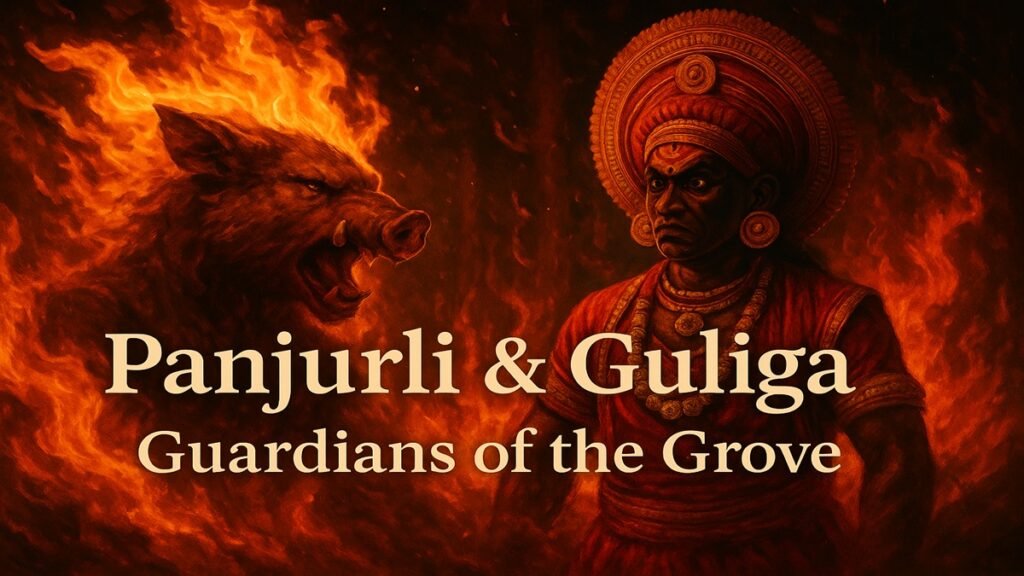

Panjurli & Guliga: Guardians or Deities or Daiva at the heart of Kantara Explained in English and Hindi

About Panjurli & Guliga In English:

I) Panjurli — the Courageous Boar-Guardian

Farmers across Tulu Nadu love Panjurli, protector of fields and forest edges. In popular lore, a celestial boar is spared and sent to earth as a guardian; the animal spirit pairing (wild boar ↔ Panjurli) encodes both respect for the wild and the need for balance with agrarian life. Panjurli is invoked to straighten what has gone crooked—especially when deceit or neglect threatens the village’s grain, water, or peace. MAP Academy

Iconic qualities of Panjurli:

- Protects crops and boundaries at the village’s forest edge

- Favours honesty, punishes deceit

- Associated with courage and moral clarity

II) Guliga — The Boundary and Oath Keeper

Guliga stands for the gravity of promises and the seriousness of borders (literal and moral). Paired rites with Panjurli enact care and consequence: compassion for the village and uncompromising justice when vows are broken. Together they teach a simple ethic with cosmic reach: land is a sacred trust; truth is a binding force.

Why does the pairing feel so satisfying on screen and in life? Because it mirrors how healthy communities work—kindness with accountability, generosity with courage.

Iconic qualities of Guliga

- Embodies niyama (rule/discipline) and maryādā (boundary/dignity)

- Witnesses oaths; rebukes falsehood

- Restores balance when power is misused

Why the pairing matters:

Where Panjurli protects, Guliga polices; where Panjurli nurtures, Guliga enforces. The dyad is not a clash but a complement—like two hands that together can carry the weight of a community’s hopes.

Story of Panjurli, Guliga and Bhoota Kola In Hindi:

I) पंजुरली — साहसी वराह-रक्षक ( Panjurli — the Courageous Boar-Guardian)

तुलुनाडु की पवित्र भूमि पर पंजुरली (पंजुरली देवता) का नाम श्रद्धा और आस्था के साथ लिया जाता है। किसानों और ग्रामीणों के लिए यह देवता केवल एक प्रतीक नहीं, बल्कि खेती और जंगल की सीमाओं का रक्षक आत्मा है — जो मानव और प्रकृति के बीच संतुलन बनाए रखने का प्रतीक है।

लोककथाओं के अनुसार, पंजुरली एक दैवी वराह (सूअर) था जिसे स्वर्ग से पृथ्वी पर भेजा गया था ताकि वह धरती की रक्षा करे। कहा जाता है कि जब छल, बेईमानी या उपेक्षा के कारण गाँव में अनिष्ट फैलता है, तो पंजुरली की पूजा की जाती है ताकि सत्य और न्याय फिर से स्थापित हो सके।

यह कथा केवल एक धार्मिक आस्था नहीं, बल्कि एक जीवन-दर्शन है — जो बताती है कि समृद्धि तभी संभव है जब मनुष्य प्रकृति के साथ सामंजस्य में जीए। पंजुरली साहस, ईमानदारी और नैतिक शक्ति का प्रतीक है — जो हमें हर परिस्थिति में सत्य के मार्ग पर चलने की प्रेरणा देता है।

पंजुरली के प्रमुख गुण

- खेती और जंगल की रक्षा करने वाला देवता: फसलों और प्राकृतिक सीमाओं की सुरक्षा का प्रतीक।

- सत्य का पक्षधर: ईमानदारी को सम्मान देता है और छल करने वालों को दंडित करता है।

- साहस और निष्ठा का प्रतीक: अन्याय के विरुद्ध खड़े होने की शक्ति प्रदान करता है।

II) गुलिगा — न्याय और संतुलन के दैवी रक्षक ( Guliga — The Boundary and Oath Keeper)

तुलुनाडु की लोककथाओं में गुलिगा (गुलिगा देवता) को एक प्रचंड और न्यायप्रिय आत्मा के रूप में पूजा जाता है। जहाँ पंजुरली करुणा और संरक्षण का प्रतीक है, वहीं गुलिगा न्याय और अनुशासन का दैवी रूप माने जाते हैं। यह देवता संतुलन बनाए रखने वाले शक्ति-स्रोत हैं — जो अच्छे कर्मों को आशीर्वाद और अधर्म को दंड देते हैं।

लोकविश्वास के अनुसार, गुलिगा की उपासना केवल भय से नहीं, बल्कि सम्मान और न्याय की भावना से की जाती है। उनका स्वरूप उग्र है, पर उद्देश्य सदा पवित्र — अन्याय मिटाकर समाज में नैतिक व्यवस्था की स्थापना करना।

गुलिगा देवता हमें याद दिलाते हैं कि सच्चा संतुलन केवल तब संभव है जब शक्ति और करुणा, दोनों साथ चलें।

गुलिगा के प्रमुख गुण

- न्याय के रक्षक: सत्य का समर्थन करते हैं और अधर्म का विनाश करते हैं।

- शक्ति और संतुलन के प्रतीक: मानव और देवत्व के बीच संतुलन बनाए रखते हैं।

- अंधकार में प्रकाश का रूप: भय को मिटाकर आत्मबल और स्पष्टता प्रदान करते हैं।

आध्यात्मिक अर्थ

गुलिगा केवल एक देवता नहीं, बल्कि एक जीवंत दर्शन हैं — यह बताते हैं कि जीवन में शक्ति तभी अर्थपूर्ण होती है जब उसका उपयोग सत्य और संतुलन की रक्षा में किया जाए। उनकी कथा हमें यह सिखाती है कि असली भक्ति केवल पूजा नहीं, बल्कि नैतिक जीवन जीने की कला है।

III) भूता कोला — आत्माओं का दैवी नृत्य और श्रद्धा का पर्व (Buta kola Festival in Hindi)

कर्नाटक के दक्षिणी तटों पर जब रात्रि का अंधकार फैलता है, तब हवा में ढोल-नगाड़ों की गूँज उठती है — यह है भूता कोला (Bhoota Kola), एक पवित्र अनुष्ठान जहाँ मानव और दैवी शक्तियाँ एक हो जाती हैं।

यह केवल एक नृत्य नहीं, बल्कि ईश्वरीय उपस्थिति का जीवंत अनुभव है।

भूता कोला को “दैवी नृत्य” कहा जाता है क्योंकि इसमें पूजा करने वाला व्यक्ति (कोला कलाकार) स्वयं दैवी आत्मा का वाहक बन जाता है। जब वह मंच पर आता है, तो उसके शरीर और शब्दों के माध्यम से पंजुरली या गुलिगा जैसी आत्माएँ बोलती हैं। इस क्षण में देवता, मानव और प्रकृति — तीनों के बीच की सीमाएँ मिट जाती हैं।

भूता कोला का उद्देश्य

भूता कोला का मूल उद्देश्य है — “संतुलन की पुनर्स्थापना।” यह गाँव और जंगल के बीच, मनुष्य और प्रकृति के बीच, शक्ति और भक्ति के बीच सामंजस्य स्थापित करता है।

ग्रामीण समाज में भूता कोला केवल धार्मिक आयोजन नहीं, बल्कि सामाजिक न्याय का माध्यम भी है। जब कोई विवाद या अन्याय होता है, तो लोग इस अनुष्ठान के माध्यम से दैवी निर्णय प्राप्त करते हैं। यहाँ सत्य को देवता के मुख से कहा जाता है, और उसका पालन पूरे गाँव को करना होता है।

भूता कोला की प्रमुख विशेषताएँ

- दैवी संवाद का पर्व: जहाँ आत्माएँ मानव माध्यम से बोलती हैं।

- न्याय और आस्था का संगम: समाज में सत्य और अनुशासन स्थापित करता है।

- प्रकृति और कृषि से जुड़ा उत्सव: फसलों, जंगलों और नदियों की रक्षा की कामना की जाती है।

आध्यात्मिक अर्थ

भूता कोला हमें यह सिखाता है कि भक्ति केवल मंदिरों में नहीं, जीवन के हर कर्म में बसती है। यह अनुष्ठान याद दिलाता है कि दैवीय शक्ति हमारे भीतर भी है — बस उसे जगाने के लिए सत्य, श्रद्धा और सेवा की आवश्यकता है।

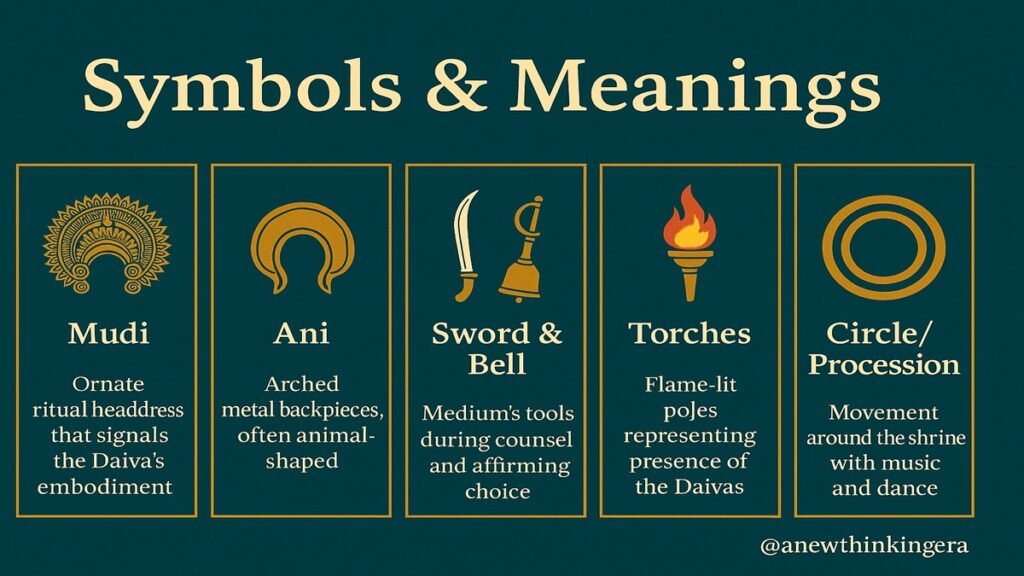

Material language In Bhoota Kola: what the eye sees and what it means:

- Mudi (headgear), ani (halo), face-painting: signals indwelling presence and lineage of the Daiva. (MAP Academy)

- Torches, sword, bell: purification and truth-testing—the arena becomes a court of conscience. (Sahapedia)

- Music ensemble: nadasvaram with tembere/chende, cymbals, and pipes—escalating rhythmic cycles guide trance and communal focus. (Academia)

- Procession and circle dance: re-maps the village–forest boundary, ritually restating who protects what, and why. (MAP Academy)

The language of costume, metal, fire, and sound:

- Mudi (headgear) and Ani (halo): Neither “props” nor mere heritage craft, these are threshold signs—once donned, the medium is a vessel. The silhouette isn’t arbitrary; it announces the Daiva’s lineage and the shrine’s authority. MAP Academy

- Sword, bell, torches: Instruments of clarity. In the arena’s circle, light and sound test truth, purify space, and call witnesses seen and unseen.

- Drums, pipes, cymbals: The soundscape isn’t background music—it is ritual choreography for the heart. Rhythmic cycles mark phases of arrival, counsel, and blessing. (If you feel your chest thrum during the crescendo, that’s partly the point.)

- Procession & circling: When the medium traces the perimeter, he isn’t “blocking a scene”—he’s redrawing the village-forest boundary, reminding everyone where stewardship begins and how community is held together.

What happens here besides worship: justice, peacemaking, and social repair

A striking feature of Bhoota Kola is its jurisprudence. Petitions are heard openly; oaths are taken in the Daiva’s presence; verdicts are moral commitments for the coming year. Older communities describe the night as a “sacred court”—not replacing civil law but binding consciences in ways paperwork cannot. In the best moments, the rite offers truth with dignity: even rebuke is framed toward repair, not humiliation. Wikipedia

This is why Kantara resonated with audiences beyond the coast. Many viewers recognized a hunger for accountability that is public yet compassionate.

Ecology at the Center: Forests, Fields, and the Spirits Who Keep Them

Long before “climate” and “sustainability” became global keywords, Tulunadu’s rites encoded an ethic of care for place. Shrines live beside groves; paddanas recollect springs and field boundaries; Daivas guard against greed and forgetfulness. In this view, the forest is not merely a resource; it is a relative—a realm with which humans must stay in right relationship.

When a community says “the spirit will not allow it,” they are not being anti-modern; they are articulating a moral contract with the living world. The rite turns ecology into daily habit: don’t pollute the stream, don’t break your oath, don’t grab more than you can steward. This is environmental education without a lecture—sung, danced, remembered.

In other words, when a community says “the spirit will not allow it,” they are not being anti-modern; they are articulating a moral contract with the living world.

Kantara: cinema as bridge to Kantara Mythology (and why it matters)

Films cannot replace rites, but sometimes they can open a door. Kantara did exactly this—inviting viewers to feel the music, fire, and ethics of Bhoota Kola. Recent analyses situate the film within conversations about decolonizing knowledge, arguing that it circulates indigenous wisdom in a medium people everywhere understand.

If you left the theatre with goosebumps, it wasn’t only the boom of drums; it was the recognition that memory is a kind of power. Rupkatha

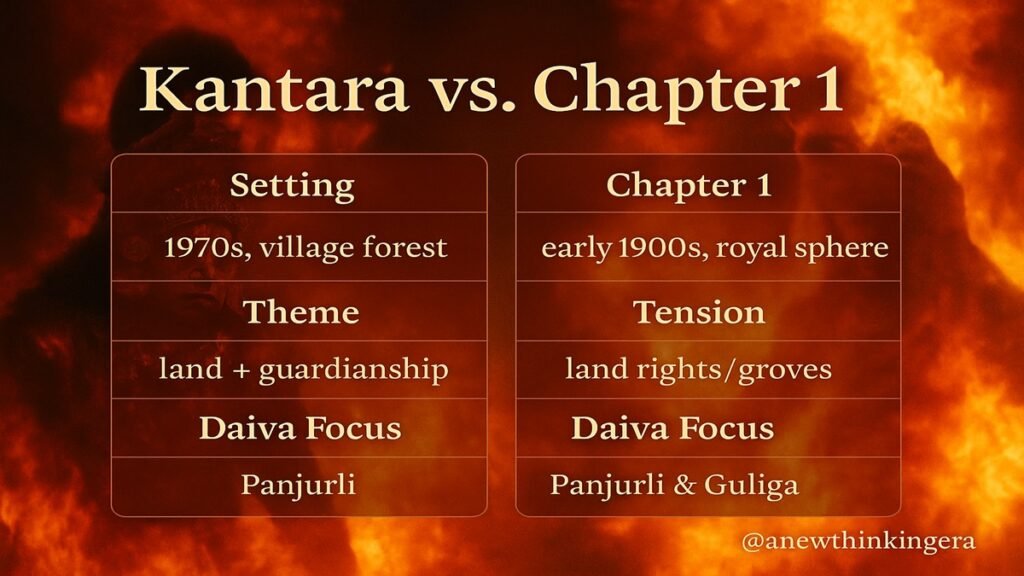

Here’s a quick brief of both films—what they are, what they’re about, and why they liked by the audience.

i) Kantara (2022) — The original breakout

- What it is: A Kannada-language action-drama written, directed by, and starring Rishab Shetty; produced by Hombale Films. It became one of the highest-grossing Kannada films ever (₹400–450 cr worldwide, reported). (Wikipedia)

- Story (no big spoilers): Set in coastal Karnataka, the tale weaves a land dispute and class conflict with Bhoota Kola/Daiva traditions. A brash villager (Shetty) clashes with a principled forest officer; the conflict culminates in a spiritually charged, ritual climax tied to Panjurli and Guliga (guardian spirits). (IMDb) Present-day conflict where the covenant is tested—land rights, power, and ritual authority collide.

- Why it resonated in audience: The film fused high-energy action with a visceral portrayal of local ritual, ancestry, and ecological ethics—turning a regional story into a national conversation. (Wikipedia)

ii) Kantara: Chapter 1 (2025) — The Prequel

- About Kantara: Chapter 1 (2025): A prequel set in an earlier era, again written/directed by Rishab Shetty. It expands the lore and origin of the Daiva traditions introduced in the first film. Kantara: Chapter 1 (2025) Released on October 2, 2025 (Gandhi Jayanti/Dussehra). (Wikipedia)

- Setting & focus of Movie : Period epic in pre-colonial coastal Karnataka (reports link it to the Kadamba era), exploring the deeper myth-history around Bhoota Kola and the community’s ancestral covenant with land and spirits. (Wikipedia)

- Reception & box office Reaction: Early trade coverage and entertainment press reported a very strong opening and rapid climb on 2025 charts (multiple reports place it among the year’s top grossers). (The Times of India)

- In the news: People talked about everything—from big fan celebrations to a funny mistake spotted in a song scene (a modern plastic water can). It went viral but didn’t slow the film down. (The Times of India)

What connects both films:

- Core theme: A covenant between people, land, and guardian spirits—with Bhoota Kola as the cultural heart. The prequel zooms out in time to show how that covenant was forged; the Kantara 2022 film showed what happens when it’s tested. (Wikipedia)

If you want, I can add a short “watcher’s guide” (key characters, timeline, glossary) you can place as a sidebar in your article.

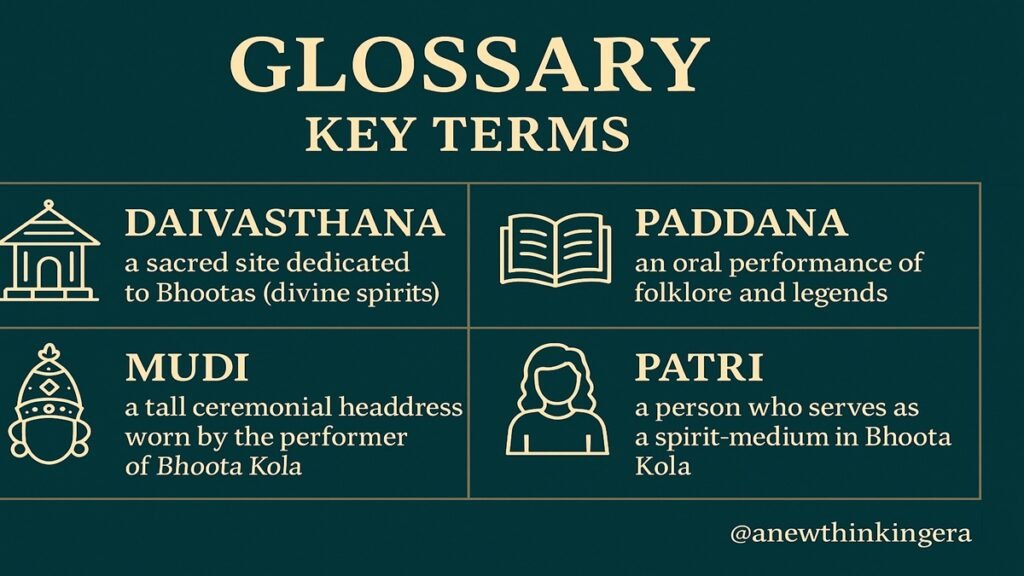

Know About Terms Related to Sacred Kantara Mythology:

Here term used in Kantara Mythology is briefly explained-

- Daiva / Bhūta: Guardian spirit; in the films, Panjurli (boar guardian) and Guliga (oath/boundary keeper) are central.

- Bhoota Kola / Daiva Nema: Night-long ritual where a hereditary medium (pātri) embodies the Daiva and offers counsel/justice.

- Guttu: Patron lineage traditionally responsible for sponsoring local rites.

- Paddana: Oral epic sung during rituals, narrating origins and duties.

- Mudi / Ani: Towering headgear and halo signifying descent/embodiment.

- Forest–Village–Spirit triad: The moral map of the films; harm to one realm disturbs the others.

- Panjurli & Guliga: Paired guardians symbolizing care and consequence, truth and boundary-keeping, agriculture and justice. MAP Academy

Misconceptions, gently corrected about Kantar Mythology:

i) “Is this devil worship?”

No. That phrasing comes from colonial misunderstandings. Practitioners describe the rites as veneration of guardian spirits within a Hindu regional framework, intimately tied to ancestors, place, and dharma (ethical order). MAP Academy

ii) “Isn’t it just theatre?”

For insiders, it is embodiment (a presence arrives), counsel, and oath. Scholars may analyze its aesthetics, but within the village the primary category is worship and justice, not art performance. Sahapedia Map

iii) “Are there fixed rules for offerings?”

No single list applies everywhere. Lineage and shrine custom govern specifics, and practices evolve. The constants are honor, counsel, blessing, and the renewal of vows.

iv) “Can outsiders attend?”

Often yes—respectfully, and by following local guidance. Ask a local temple committee or cultural group. Dress simply, avoid intrusive photography, and observe from outside the sacred circle.

How to experience Bhoota Kola with reverence (if you ever get the chance)

- Ask locally to know more about Bhoota Kola

The rite is community-held; dates vary. The main season often falls between December and May, but each shrine has its own calendar and protocol. Seek a local cultural organization or temple committee rather than showing up uninvited. Sahapedia - Dress simply; to be present in Bhoota Kola

This is worship. Avoid intrusive photography, stay outside the sacred circle, and follow the directions of attendants. When the medium is in counsel, lower your voice or simply listen. - Notice the details of Bhoota Kola

The way torches are raised; the circling steps; the moment the mudi is placed; the cadence of the paddana—these are not adornments, they are the language of the rite. - Learn a little Tulu vocabulary

Words like Daivasthana (shrine), paddana (oral epic), pātri (medium), mudi (headgear), ani (halo) are small bridges into a larger world.

Why this Bhoota Kola tradition feels so alive:

There are three reasons:

1) It is radically communal.

In an era of hyper-individual lives, Bhoota Kola requires a whole village: performers, patrons, cooks, drummers, elders, children—even the absent, remembered by name in paddanas. The rite gives everyone a role and, with it, a responsibility.

2) It makes ethics tangible.

We all yearn for a world where truth matters and promises bind. Here, those are not slogans on a wall; they are vows spoken aloud in a circle of firelight, under witness.

3) It unites ecology with devotion.

Bhoota Kola says the forest is not “out there”; it is our life’s edge, and what we do at that edge makes or breaks our future. The Daivas are the village’s way of remembering this, year after year. SpringerLink+1

Respecting Local Beliefs in Kantara’s Tradition

Because Bhoota Kola is living tradition, you will meet variations—of costume, song, offerings, sequence, even interpretation. Please receive them as signs of health, not inconsistency. Belief-worlds in India have always been plural and locally tuned. This explainer aims to celebrate that richness without ranking or judging any practice. (If something here differs from what your elders taught you, honor them first—and consider this a friendly, well-meant overview.)

Conclusion: The Heartbeat Behind the Fire

Kantara didn’t invent Bhoota Kola. It reminded us that India’s deeper stories are not lost; they are kept—patiently—by villages, groves, songs, and the people who show up each year to renew a vow. If you’ve read this far, perhaps you wanted more than a plot synopsis. You wanted the heartbeat behind the fire.

Here it is: a world where land is sacred, truth is binding, community is refuge, and the guardians still come when called. Not to frighten, but to steady. Not to divide, but to repair. And always, to remind us that what we share—water, grain, sky, memory—is worth protecting together.

FAQ about Kantara Mythology

FAQs: Kantara, Bhoota Kola & Tulu Nadu Traditions

1) What exactly is Bhoota Kola—worship or performance?

Bhoota Kola (also called Daiva Nema) is first and foremost worship. It’s a night-long ritual where a hereditary medium (pātri) embodies a guardian spirit (Daiva) and offers counsel, blessings, and community guidance. While it has powerful visual elements, insiders treat it as sacred embodiment—not entertainment.

2) Who are Panjurli and Guliga in simple words?

Panjurli is a beloved boar-guardian associated with protection, courage, and keeping things “straight.” Guliga is the stern boundary and oath-keeper linked with justice and truth. Together, they symbolize care + consequence in village life.

3) Is Bhoota Kola the same as Theyyam or Yakshagana?

They share coastal aesthetics (costumes, drums, oral epics), but they’re distinct traditions with different ritual authority, theology, and community contracts. Bhoota Kola belongs to Tulu Nadu’s Daiva worship; Theyyam is from North Malabar; Yakshagana is theatre/dance-drama.

4) Can outsiders respectfully attend a Bhoota Kola?

Often yes—if invited or guided locally. Dress modestly, avoid flash/close-up photography, stay outside the sacred circle, and follow directions from shrine caretakers. Remember: this is worship and a community forum, not a show.

5) What’s the connection between Kantara and real traditions?

Kantara dramatizes a world rooted in Tulu Nadu’s living rituals. The film uses Panjurli–Guliga and Bhoota Kola as its moral center, highlighting the covenant between people, land, and guardian spirits.

6) Does every village follow the same steps and offerings?

No. Practices vary by shrine, lineage, and region. Sequence, songs (paddanas), offerings, and dates can differ. The constants are reverence, counsel, and renewing community duties.

7) Are Panjurli and Vishnu’s Varaha the same?

Some devotees see resonances (both are boar forms); others keep them distinct within plural Hindu theologies. Local practice comfortably holds multiple viewpoints with respect.

8) When is the Bhoota Kola season?

Calendars vary by shrine, but many ceremonies in coastal Karnataka occur between December and May. Always check locally; dates are set by tradition and community needs.

9) What does the “possession/embodiment” moment mean to devotees?

It’s the recognized descent of the Daiva into the medium—marked by costume, headgear (mudi), music, and a shift in speech/conduct. From this point, the medium’s words are received as the Daiva’s counsel.

10) What is Kantara: Chapter 1 about (spoiler-safe)?

It’s a prequel exploring the earlier era that forged the covenant shown in Kantara. Expect a period setting, deeper lore around Daivas, and how community, land, and oath became inseparable.

Disclaimer (Belief-Friendly & Non-Infringing):

This article presents a respectful, good-faith overview of Bhoota Kola/Daiva traditions and related cultural concepts as discussed in public sources. It is intended for education and cultural appreciation, not for theological authority, ritual instruction, or legal advice.

This article is offered for education and cultural appreciation. It presents beliefs as held by communities in Tulu Nadu and related regions, with sincere respect for all traditions. Interpretations are generalized; individual shrines and lineages may differ. No claim is made that could negate or rank religious experiences. The intent is positive, non-derogatory, and non-infringing.

- Respect for belief & variation: Rituals, paddanas (oral epics), terminology, offerings, and protocols may differ by village, shrine, lineage, season, and family custom. Readers should defer to local custodians, elders, and temple committees for practice-specific guidance.

- Sources & accuracy: Historical and cultural points are summarized from publicly available materials and community descriptions. While care has been taken to avoid errors, nuances may be simplified; any mistakes are unintentional.

- No endorsement or affiliation: References to films (including Kantara and Kantara: Chapter 1), producers, or artists are for contextual, informational purposes only. This site is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or sponsored by the rights holders. All trademarks and copyrights belong to their respective owners.

- Imagery & media: Illustrative images/graphics are used to aid understanding. If any image or description unintentionally misrepresents a tradition, please contact us for prompt review or correction.

- Community first: If content here differs from what your elders or local priests teach, please honor community guidance. The intent is positive, non-derogatory, and non-infringing.

Respect note :

This explainer presents how communities themselves describe and enact these rites, plus peer-reviewed cultural scholarship. It neither judges nor ranks traditions; the goal is admiration and understanding.

Sources for key points:

- Ritual form, paddana role, possession/justice functions, performer lineages: MAP Academy; Sahapedia; Baindur (JSTOR); PARI & cultural explainers. (MAP Academy)

- Panjurli–Guliga in Kantara, ecology & decolonial readings (recent scholarship): MDPI Religions; ResearchGate preprint. (MDPI)

- Paddanas as oral epics & historical memory of Tulunadu: Oral Tradition journal; studies on women-centered paddanas. (Oral Tradition)

- Types of worship (Kola/Nema/Bandi/Agelu-Tambila) and glossary: summary overviews collating standard typology. (Wikipedia)

Contact for corrections/concerns: Connect with us from contact us section.

Reena Singh is the founder of A New Thinking Era — a motivational writer who shares self-help insights, success habits, and positive stories to inspire everyday growth.